Lessons in Writing Steampunk from Geneology

by Exhibiting Author Laurel Wanrow

I’ve been asked why I chose to locate my steampunk series, The Luminated Threads, in the countryside instead of London or another city, the gritty setting of most steampunk fantasies.

Well, I’ve never been to London, and I’ve never lived on a farm either. Or operated steam machinery, or concocted a magical potion. While fantasy writing is rarely about ‘write what you know,’ it is nice to have a basis for your imaginings. My dad lived on a farm, and his dad owned and ran steam engines. Through the family stories my dad and his sister tell, I could more easily imagine life on a farm working with those big engines than any adventure in London’s back alleys.

My grandfather, Herbert F. Wanrow, was a first-generation American born in 1889 to a farming family in eastern Nebraska. Typical of most young men, he liked fancy cars…and needed an income to get them.

By the time Herb reached his twenties in the 1910s, he was selling farm machinery, but that was seasonal work. Herb purchased a sawmill to keep work going into the fall and winter and, to power it, he bought a steam engine.

Pouring over our photos, I was fascinated by this business that these days most of us only see the results of in Home Depot. My grandfather owned the only steam engine and sawmill in the area, employing a full-time fireman to feed wood—usually the endless supply of slabs—into the engine’s firebox. Another helper filled its two water tanks from a water tank on a wheeled carriage, and kept that water tank refilled from the closest source. Word of Herb’s skill as a sawmill operator spread, but the detail that really caught my attention was that most of the time he would take his sawmill to people.

I’d never heard of a portable sawmill, but my aunt reminded me that in those times transporting the sawmill was easier than hauling the logs for a building’s worth of lumber to Herb’s farm—and then back again! However, I learned ‘easier’ was relative.

Herb and his fireman would set off in the morning with the steam engine pulling the entire rig: sawmill on its wheeled platform, a wagon filled with slabs and a full twelve-foot long water tank mounted on iron wheels—just as we’d begin a road trip with a full gas tank.

The steam engine was powerful, but slow, travelling three to four miles per hour. Steering wasn’t ‘power steering’ but a chain running from the steering wheel to each front wheel to change directions. They had to stop to stoke the fire, add wood, and add water to the steam engine, which meant unhooking and bringing the water tank around each time. It’d take most of the day—and all of the water—to drive to a place they frequently set up, five miles away. Once there, the equipment was unloaded and the sawmill set up again.

At this point in my aunt’s story, I noticed each photo showed a large crew of workers—but Herb only hired the two helpers. The sawmill and steam engine had to be aligned, rails and a carriage to move the logs situated, a pit dug to collect the sawdust, water tanks refilled. The labor beforehand and during the sawmilling was carried out by the customers, their sons, their hired hands and their neighbors.

A lot of steampunk stories seem to be romanticized, making machinery operation sound easy—the heat, fuel needs and labor to run them glossed over. Listening to my family stories drove home the teamwork involved, and the sense of community. This helped me reconfigure a few realities I wanted to get right in my steampunk story.

For example, once the heavy, slow steam machinery was out in the fields, my farmworkers would not be returning it to the outbuildings each night. I gave them ‘equipment sheds’ for temporary storage. The shapeshifter hero’s opening scene is there, chasing one of the mysterious pests through the spindly legs of the stored clockwork machinery.

In an early draft, I had workers levering a hand pump to send water to the tank of a two-story tall machine—through a hose. (What was I thinking?) After I learned that my grandfather used the power of a windmill to fill his water sizable water tank, I immediately put up one on Wellspring Farm (Easy for me say, er, write!) and added a rolling tank to supply the water, via pipes.

Most importantly, I didn’t worry about having all my characters knowledgably about mechanics. In my story, as in real life, not everyone has the same skill set, but everyone’s help is needed.

Herb Wanrow operated his sawmill every winter from the late 1910s to the 1940s. After a couple of seasons, he achieved what he set out to do: he was able to purchase a new car, a 1922 Star Car. Next, he bought a second steam engine and a threshing rig. But that’s another story!

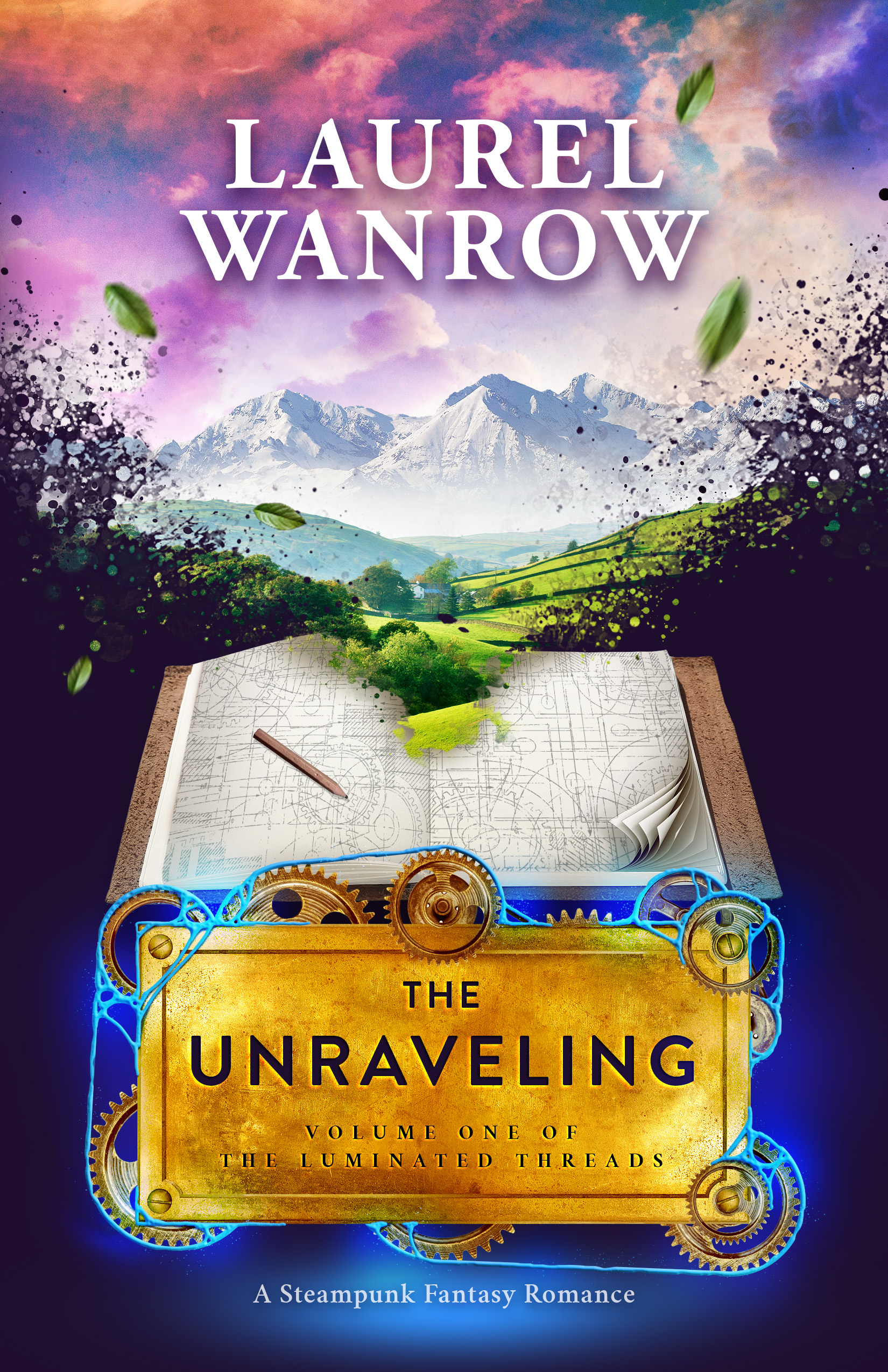

Laurel Wanrow has dabbled in genealogy since high school, recording family history tales from both sides of her family and her husband’s. Three volumes of her steampunk fantasy romance are available—The Unraveling, The Twisting and The Binding—all set in Victorian England in a rural valley of shapeshifters and magic. Visit her at the Gaithersburg Book Festival, or online at www.laurelwanrow.com.

Laurel Wanrow has dabbled in genealogy since high school, recording family history tales from both sides of her family and her husband’s. Three volumes of her steampunk fantasy romance are available—The Unraveling, The Twisting and The Binding—all set in Victorian England in a rural valley of shapeshifters and magic. Visit her at the Gaithersburg Book Festival, or online at www.laurelwanrow.com.